Sinéad Mangan-Mc Hale Linked-In profile

A decade-by-decade snapshot of the UK’s approach to migration

The second article giving a decade-by-decade snapshot of the UK’s approach to migration reviewing some of the key happening during the1970s, 80s and 90s.

The 1970s

The decade saw the introduction of decimalisation, the UK joining the European Union, the Queen celebrating her silver jubilee and the election of the first female Prime Minister.

Meanwhile, immigration controls continued to tighten in the 1970s, but the increasing demand for overseas health workers continued. In fact, by 1971, The Guardian newspaper estimated that 12% of nurses in the UK were Irish nationals. However, with immigration continuing steadily, there was growing negativity and resentment from British society. The welcome extended to citizens from the Commonwealth had brought an unexpected influx of migrants. People’s positive opinions of this situation changed following misleading reports and negative media coverage.

Immigration was the cornerstone of the Conservative party manifesto for the 1970’s election. As a report on the Law Teacher website recounted, the Conservatives, upon election, introduced the Immigration Act 1971, a single system that would control the arrival of people to the UK and included the need for a work visa for Commonwealth citizens.

However, this act did not prevent the arrival of “refugees” due to the Ugandan Asian Crisis in 1972 when Idi Amin expelled its entire Asian community. The Conservative Leader and Prime Minister stood fast to Britain’s commitment to refugees (albeit those with British passports), declaring that the country had a moral and legal responsibility to take in those with British passports. It was a sign of a changing mood; Britain would welcome asylum seekers but would exert more control over those coming in search of work.

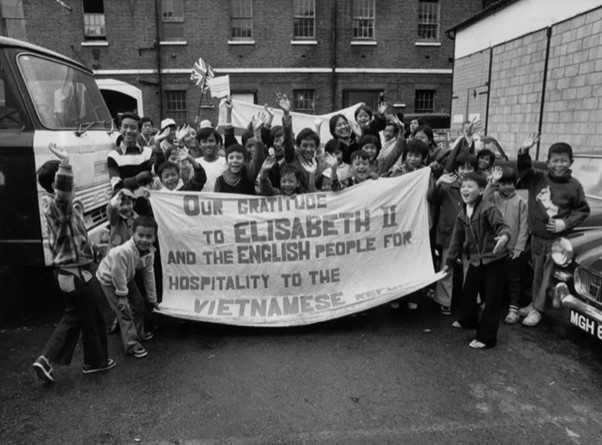

In 1975, following the end of the Vietnam War and the unification of North and South Vietnam under a brutally oppressive Communist regime, thousands of people fled the country. Desperate men, women and children were packed onto small overcrowded boats and were open to attack from pirates or death by dehydration, starvation and drowning. They became known as “the boat people”, and according to Refugee History, “around 19,000 Vietnamese refugees were resettled in Britain between 1975 and the 1990s”. The refugees arrived in the UK amid high unemployment and a housing shortage, making their integration into British society even harder.

The 70s continued to show a marked increase in racism from some elements of British society. The National Front, founded in 1967, increased its profile during this decade with marches, which often turned to violence, demanding the repatriation of immigrants. The most notable of these marches was on June 15 1974, in Red Lion Square, when the far-right fascist organisation clashed with anti-fascist groups, resulting in the death of an onlooker.

And racial abuse, regrettably still occurring today, was hurled at footballers. A Black History Month: racism in football from the House of Lords Library examined the history of racism in football and recounted an interview of former West Bromwich Albion footballer Brendon Batson with The Guardian

“We’d get off the coach at away matches, and the National Front would be right there in your face. In those days, we didn’t have security, and we’d have to run the gauntlet. We’d get to the players’ entrance, and there’d be spit on my jacket or Cyrille’s shirt. It was a sign of the times. I don’t recall making a big hue and cry about it. We coped. It wasn’t a new phenomenon to us.”

The 1980s

The 1980s was a period of economic volatility. The decade started in recession, but from the mid to late eighties, the economy boomed, and the era of the “yuppies”’ emerged. The slump in neighbouring Ireland, which saw an estimated 75,000 people leave its shore between 1981 – 1986, brought an influx of not only manual workers but college graduates to the UK. Immigrants continued to flow mainly from Asia and commonwealth countries, particularly doctors and nurses, to support the NHS.

The early 1980s saw more significant restrictions on claiming British citizenship with the 1981

British Nationality Act tightened the citizenship criteria and distinguished British citizens and British Overseas Territories citizens. At the same time, there was much debate about bogus marriage claims to allow foreign spouses to come to the UK. Spouses were subject to racial and cultural abuses, and the government was accused of insensitivity in their questioning methods. New immigration rules introduced in 1983 sought to clarify the issue.

In 1988, TGIUK supporter Lord Alf Dubs, himself a refugee from Czechoslovakia, became Chief Executive of the British Refugee Council and led the organisation until 1995. The council recorded just some of the trends of refugees facing turmoil in their own countries seeking asylum in the UK during the eighties. .

- Early 1980s – around 20,000 Iranians (mostly students) and 1,500 Poles were granted permission to stay in the UK due to the situation in their country of origin

- Mid to late 1980s – refugees from Ghana, Ugandan and Somalia requested asylum in the UK

- 1989, more than 3,000 Kurds came to seek asylum

The 1990s

The 1990s saw an explosion in high tech as computers and mobile phones, albeit very large, became more popular. The Labour Party came into power, and the death of Princess Diana stunned not only the UK but the entire world.

The 1990s also saw an explosion in both immigration and emigration in the UK. The signing of the Maastricht Treaty was a passport to live and work within the EU without restrictions, as historian Keith Lowe wrote for the BBC in 2020.

“In 1992, the UK joined other EU nations in signing the Maastricht Treaty on European integration. This treaty granted all EU citizens equal rights, with the freedom to live in any member state they chose. In the following decade, tens of thousands of EU citizens came to live and work in Britain. Few people protested, possibly because these newcomers were balanced out by the tens of thousands of British people who moved away to other parts of the EU. Nevertheless, a new principle had been set. As the country once held an open-door to the Commonwealth, it now held an open-door to the European Union.”

There was another political shift in attitude towards migrants when the Labour Party came into power in 1997 after decades of Conservative rule. According to an article in the Migration Policy Institute

“When the Labour Party came to power in 1997, immigration policy shifted course. Emphasis was placed on “selective openness” to immigration. Limiting and restricting immigration ceased to be a pillar of UK policy, and focus was on accommodation for workers and students, particularly those from the European Union.”