The children and grandchildren of the migrants who settled here from the 1950s to today don’t need a label; they are a seamless part of the wonderful cultural tapestry that makes up our nation.

We live in a global society that wants to label us – migrants, asylum seekers, Black people, LGBTQ+, feminists, disabled, Muslims, Christians, on and on. Some people embrace such labels as it gives them a sense of belonging to a community. However, others feel uncomfortable with the need to band humans into separate groups identified by nationality, culture, tendencies, or preferences. To them, what is more important is being comfortable and confident in their own identity. Goody, a published author, is fiercely proud of her identity. Indeed, the opening lines of her poem, British Punjabi, published in the TogetherintheUK anthology of migrant writings, Hear Our Stories, starts beautifully with the lines,

I am a second-generation Punjabi.

I won’t be a clone

I won’t erase a culture of my own.

Alongside being British,

I won’t take the Punjab out of my bones.

In our conversation, she reaffirmed the importance of owning your identity and gave her opinion on the use of the term second generation migrant children, I don’t think we need to label a “second generation” child versus an “English” child. A child is a child regardless of skin colour or origin. Terms like these often create division and encourage segregation.

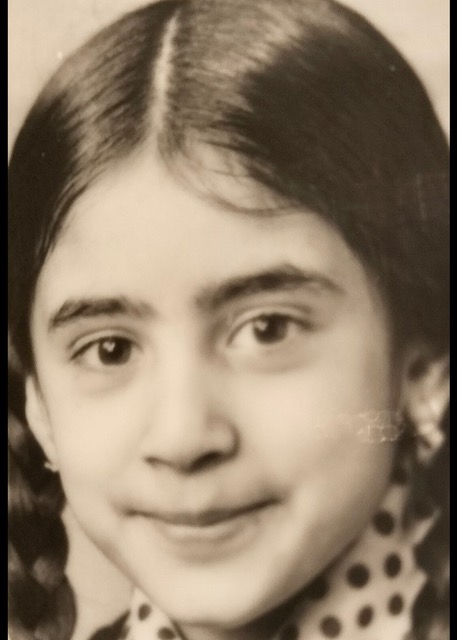

Goody is well entitled to discuss the life of a child of migrant parents. Her father came to the UK in 1956 as an 18-year-old immigrant from Punjab in India, and her mother joined him six years later. Goody was born in Leeds in 1967 and lived in a diverse community with migrants from Punjab, Jamaica, Pakistan, Poland, and Ireland, who all supported each other. Her parents spoke their native language, and Goody and her twin brothers grew up speaking both Punjabi and English fluently. She proudly celebrates her heritage and treasures her family history.

Children of migrant parents can experience a phenomenon known as “parental sacrifice guilt” as they recognise their parents’ sacrifices to make a life in the UK. Some may also face additional pressure to live up to their parent’s expectations as a form of reciprocation for that sacrifice. Goody is fully aware of the sacrifices made by her parents and many other migrants in leaving family and friends behind and, in some cases, selling precious possessions to pay for the journey to the UK. However, rather than feeling guilt, Goody proudly speaks of her parents honouring their sense of responsibility to their family in Punjab. Her parents worked hard to care for their family in the UK while sending money back home to their own parents, some of which was used to pay for Goody’s uncle’s education.

One of the more common issues facing children of migrant parents, particularly those parents who come from a very traditional and religious-centric culture, is the balancing act between the old and new culture. Conflicts within families due to generational differences are common, but when you add cultural differences, the dynamics can be volatile. While many migrants embrace the new host culture and maintain a solid connection to their roots, some migrants strive to preserve their traditional way of life. Goody discusses the issue of “mixed marriages” and tells us of a situation close to her family.

For women in my culture, marrying outside the culture and religion was cause for a great deal of shame and pain for their families, as daughters, in particular, were the honour of the family. They were considered to be “bad girls”. My Sikh cousin married a Muslim in the 1980s and was ostracised by her family for many years. However, nowadays, our blended culture is more accepting of interracial relationships and marriages, and both sides of the families interact with each other, enjoying the differences in each other’s cultures.

Marius Turda spoke about racism as being the real pandemic in an interview with TGIUK, and many people reported increased racist comments during and after Brexit. Goody vividly remembers being asked, “When are you going back home?” the day after the vote. However, it was the racist attitudes when growing up and which her parents faced at the time of the Rivers of Blood speech, a speech which ignited racial animosity, particularly from Skinheads and the National Front, towards migrants that impacted her the most. Indeed, many children of migrants found that as they grew up in the mainstream culture, at times, there was a role reversal between child and parent, as the young protected their parents from racist behaviour.

I always felt I needed to protect my parents whilst growing up. They were vulnerable because of the language barrier and were often made fun of because of their accents and how they spoke broken English or when conversing with their friends or children in Punjabi. People also criticised or complained about our national attire. Many Punjabi men wore English dress, but the women wore predominantly traditional Punjabi clothes and were often ridiculed for doing so.

Faced by such racism in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, right up to today, it is understandable why parents want to protect their children and why some shelter them from interactions outside of their community. Sadly, racism exists even amongst children, and no parent wants their child to be subject to teasing or worse, because of the colour of their skin, their traditional attire or their language skills. Added to that is the fear that external influences would dilute their own culture. Luckily, many first generation parents are agile in their thinking and open their hearts and minds to the many nationalities living in the UK. Goody recalled a similar situation in her family.

When I was growing up, my parents were quite wary of us becoming friends with children from other cultures because they were keen to retain our culture. They mellowed over time and had friends from different cultures themselves who remained lifelong friends. When my father passed away, his friends from various cultures came to his funeral to pay their respects. It was touching to hear their kind words about my dad at his funeral.

Today, Goody enjoys a mixed group of friends: English, Punjabi, Jamaican, Irish, Pakistani, and Polish, amongst many others.

This article started with the importance of identity and, as we know, the issue of labelling people, specifically the abuse of the word “migrant” in a time of increasing negativity amongst some, often as a result of misinformation, simply reinforces stereotyping. Goody proudly identifies as a British Punjabi. She celebrates her British and Punjabi heritage, knowing that, in her words, we are all one race.

To read more about the lives and impacts of migrants in UK society, go to TogetherintheUK.

To purchase a copy of Hear Our Stories, an anthology of migrant writings compiled by TogetherintheUK, go to Support Us.