Author: Alison Hramiak

Standfirst

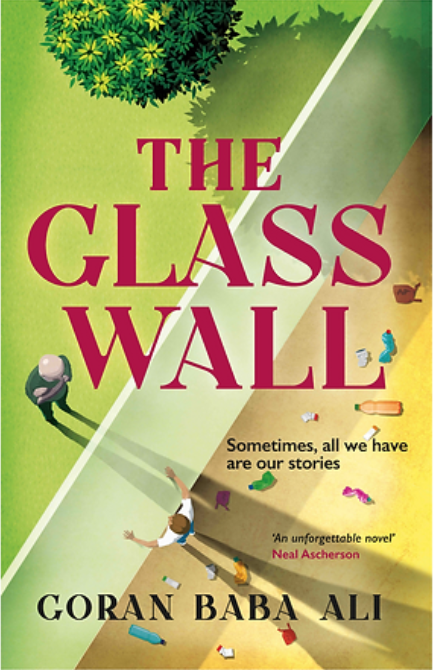

This is a review of a book that tells the story of a teenage refugee who must re-live the pain of his past to enter a land waiting behind a glass wall. Alison Hramiak tells you why you should read this important book. Afsana Press | www.afsana-press.com

This is a very clever book.

This immense novel pulls you in from the start, and for me, is reminiscent of dystopian science fiction from the 1970s, (or earlier) in the way that it asks the reader to imagine a world of two halves, one of which is perceived to be so much better than the other. There are also echoes of other worldly fiction, such as the novel ‘Gone’ by Michael Grant, a fictional book aimed at teenagers (but readable by adults) that expands the mind in the way that ‘The Glass Wall’ did for me.

At the heart of this book is a very astute concept, a glass wall, that divides and separates, physically as well as psychologically and emotionally, and which is ever present, almost like a spirit that just won’t leave. At times, it feels like it is the wall that is the protagonist of the book, rather than Arman, and it is the latter’s relationship with the wall that looms large from every page.

The plight of refugees and immigrants, the frustrations they face speaks volumes from the pages. In striving for a better life, it is not just physical torment that they face, there is much in the way of mental and emotional anguish. You have to ask yourselves, just how desperate do you have to be, how bad is your life where you were born and live, that you feel then need to risk everything find a different life elsewhere? This exasperation and the accompanying weariness came across very clearly to me in the following lines of dialogue between Arman and the guard when discussing the sparse amount of food and water he was allowed:

How can I survive five days with only one bottle of water?

I’m really sorry, Arman! I can’t do anything about that. That’s the rule and they will not adapt it!

This mountain of bureaucracy, the inflexibility Arman faces, is, for me, a symbol of the immense hardship faced by people who only want a decent (safe) life for themselves and their loved ones.

This is a beautifully written book, with a language that is expressive and emotive, and, at times, quite lyrical in the way it imaginatively uses metaphor and simile, like pockets of poetry scattered throughout the text. For example, on the first page with the line:

‘The heat slapped his face and bare arms’

right through the book with words like:

‘It was all chaos and muddle in his head. As if an old, scratched CD was spinning inside his skull.’

For me, these serve to add even more depth to the story held within the words.

This heartfelt and perceptive imagery serves to create clear pictures in one’s mind, to take you there, to the places and people held in the pages of the book. This is an easy book to follow and to read, and one which moves along at pace, served well by the realistically emotive dialogue, and the vivid descriptions within it. There is a stark realism held in the details depicted here that the author does not shy away from, and which require one to think very sincerely and seriously about the plight of others in this world.

Throughout the novel there are endearing links to family and past life, and how this has consequences, how it has ricocheted into Arman’s present. I particularly loved the references to Arman’s grandma, and the way he talked about her, and how she was both revered and missed. From the manner in which she was described, she sounds like someone that was a true force of nature, someone to have known and loved.

Although this story revolves round Arman, the guard’s perspective is very much a pivotal part of the novel, and his thread is carefully interwoven, largely through dialogue, within the text. This is done almost to the point where you start to have some sympathy for him and his version of events. Almost.

The mentoring aspect of the narrative, towards the end of the book, is also very skillfully executed, and alludes to the way the circle turns, and the way nothing changes, letting the reader contemplate how no real progress has been made between the start and the end of the book. This is a point well made by the last line in the book in which the guard comments, with respect to new refugees seen in the distance, that:

‘I hope they have a good story’.

I think that what this book teaches us is to try and put ourselves in someone else’s shoes so that we might better understand them and the world they face. It has parallels to the glass ceiling so many women have faced for centuries, and like the glass ceiling, this glass wall shows no signs of real improvement as years go by. This novel is a hard read, bleak at times, and it does not end in a rainbow of hope and glory. But it is one that grips and one that bears a deep message within its pages – a message that resonates with too many people across too many lands and for too many centuries. In the words of the author:

‘They don’t see us. It’s mirrored on the other side’.